East Bay second Cal State foundation to file questionable tax returns

By John Hrabe

With 427,000 students and 44,000 staff on 23 campuses, the California State University System is the nation’s largest higher education system. But from Los Angeles to San Francisco, Cal State is raising tuition, cutting enrollment and campaigning for a multibillion-dollar tax hike — all while providing high salaries and lavish benefits to its top executives. “If the tax measures fail,” the Associated Press recently reported, “fall enrollment would be cut another 20,000 students and 3,000 employees laid off.”

In less than eight years, tuition has risen 150 percent, from $2,334 per year in 2004 to just under $6,000 this fall. Just don’t ask Cal State’s top executives to share the burden. The college’s trustees have doled out massive pay raises, misled the public about its executives’ compensation and now want to use nonprofit donations to supplement already excessive salaries.

College Foundations Face Minimal Scrutiny

Cal State’s official executive-compensation summary leads the public to believe that the average president receives $300,000 in pay and up to $60,000 toward housing costs. The job isn’t easy, and the high salary reflects the need to recruit top executives that can raise money for the school, among other tasks. To fulfill their fundraising obligations, Cal State argues, presidents need two things: a housing reimbursement and the authority to run a tax-exempt, auxiliary foundation. These auxiliary foundations, however, offer crucial evidence that Cal State has underreported the total amount of taxpayer-funded compensation its officials receive.

College auxiliary organizations, like any tax-exempt nonprofit, are required by law to report executive compensation on publicly available tax returns. In order to prevent organizations from hiding the true amount of executive compensation, the IRS requires the disclosure of all compensation from the nonprofit and any related organization, including “a nonprofit organization, a stock corporation, a partnership or limited liability company, a trust, and a governmental unit.”

That means every president’s taxpayer-funded salary should be disclosed on the college foundation’s tax return because it is from a related organization. The IRS regulation is designed to prevent non-profits from hiding executive compensation from other sources. Therefore, Cal State foundation tax returns can act as a way to verify the taxpayer-funded compensation disclosed by each Cal State University. Cal State foundation tax documents don’t come close to matching the numbers disclosed by the Cal State Chancellor’s Office or the State Controller’s Office.

Consider the case of Mohammad Qayoumi, the former president of California State University East Bay and current president of San Jose State University. Cal State’s website reported his East Bay starting salary at $237,072 per year, plus $60,000 toward housing costs. Yet the Cal State East Bay Educational Foundation, the nonprofit auxiliary organization the college president manages, reported that Qayoumi received zero compensation from the foundation or any related organization on federal tax returns for 2008, 2009 and 2010. The foundation’s Form 990 tax return is inaccurate and contradicts the IRS’s straightforward instructions for disclosing executive compensation.

It’s conceivable that East Bay’s missing executive-compensation data could be an inadvertent accounting error. However, East Bay’s tax returns don’t resemble the tax returns of other Cal State foundations that reported total presidential compensation. For example, Sacramento State University’s foundation tax returns for the same period include executive compensation data from both taxpayer and foundation sources.

East Bay: Non Responsive to Requests for Public Information

Cal State East Bay hasn’t responded to repeated requests for the total compensation data for the periods in question. “The IRS Form 990 tax reports filed by Cal State East Bay and available to the public on the university Web site were complete and accurate at the time each was filed,” Barry Zepel, Cal State East Bay’s Media Relations Officer, wrote to CalWatchdog on April 28. “The 990 forms include some information presented on a fiscal year basis and some on a calendar year cycle, which includes data from two fiscal years (e.g., the 990 for CY 2008 would reflect data drawn from FY 2007 and FY 2008).”

Taxpayer advocates like Senator Joel Anderson, R- Santee, aren’t buying the excuses. “CSU’s leaders are proving over and over again that they’re incapable of being good stewards with taxpayers’ money: the $400,000 executive salaries, the tapping of Foundation money to cover-up these outrageous salaries,” Anderson told CalWatchDog.com. “Now we find out that they may have committed tax fraud in the process.”

The foundations’ missing or misreported numbers bear directly on the debate about Cal State’s executive compensation. The Cal State Chancellor’s Office continues to claim that high salaries are needed to attract the best talent. Moreover, the Cal State Board of Trustees has now shifted all future pay raises to these nonprofit foundations.

“As I said last week when the chancellor proposed this new policy, it is nothing more than smoke and mirrors disguised as reform,” said State Senator Leland Yee, D- San Francisco. “The trustees are beyond tone deaf; they are either completely oblivious or simply don’t care what students, lawmakers, and taxpayers think.”

Finance Expert Qayoumi Can’t Fill Out Basic Forms

A former vice president for administration and finance and chief financial officer at Cal State Northridge, Qayoumi had impeccable credentials to sort through the foundation’s finances. However, Qayoumi couldn’t follow basic tax instructions. Two sections of the 2009 tax return clearly call for disclosing compensation from related organizations: “Column E: Reportable compensation from related organizations (W-2/1099-MISC)” and “Column F: Estimated amount of other compensation from the organization and related organizations.”

One reason to think the foundation’s numbers may not be the result of mere oversight or clerical error appears on Schedule O of the East Bay Educational Foundation’s Form 990. It describes in painstaking detail the review process officials undertook before submitting their 2010 returns to the IRS: “Form 990, Part VI, Section B, Line 11: The organization’s Form 990 is reviewed line by line by the president and treasurer and then signed by the president. After the president and the treasurer have approved the final draft of the Form 990, the organization will create a PDF of the form and email it to the members of the governing body before submission and/or due date of the form.”

East Bay is the fourth Cal State campus to report one set of compensation numbers to the IRS and another to the public. On federal tax returns for 2007, 2008, and 2009, San Jose State University’s Tower Foundation reported zero compensation paid by the organization or any related organizations to more than a half-dozen high-ranking university personnel, including the college’s president, provost, athletic director, and several vice-presidents. The California State University Office of the Chancellor understated the annual compensation of San Francisco State University president Robert Corrigan by as much as $52,787 when compared to the San Francisco foundation tax returns.

The most substantial discrepancy uncovered so far involves Cal State Los Angeles president James Rosser. He reported $515,612 in annual compensation to the IRS for the 2009 tax year. In at least five instances, including official statements from the chancellor’s office, Cal State’s website, and an independent competitive pay analysis by the Mercer Consulting firm, Cal State officials have falsely claimed or implied that Rosser’s compensation was nearly $200,000 less—an annual base salary of $325,000.

Rosser’s half-million-dollar compensation, which was reported on foundation tax documents, provides evidence that Cal State’s official compensation data is bogus. It turns out that base salary and housing benefits are only a fraction of total executive compensation, and these miscellaneous benefits represent as much as 50 percent of a college president’s base pay.

Retirement benefits alone cost taxpayers an amount greater than the state’s average per capita income. In the case of East Bay’s 2006 presidential compensation of Qayoumi, base pay and housing were supplemented by a $12,000-per-year car allowance, five weeks of annual paid vacation, 12 days of sick leave, a top-of-the-line health-care plan, dental coverage, vision care, automatic enrollment in the state’s retirement program for public employees, an annual physical examination, relocation costs and moving expenses, and “entertainment allowances.”

In 2011, Qayoumi transferred to San Jose State University, which increased his base salary to $328,200, a $91,128 raise in five years. By transferring to San Jose, Qayoumi picked up another $25,000 from the university’s nonprofit auxiliary foundation. Four Cal State officials (including Qayoumi) collect anywhere from $25,000 to $50,000 in bonuses paid by tax-exempt college foundations.

Cal State’s Ongoing Pay Scandal

Cal State’s executive-compensation woes began last July, when the university’s Board of Trustees approved a $400,000 base salary for Elliott Hirschman, San Diego State University’s new president. At the same meeting, the trustees announced a 12 percent tuition increase for the fall term. Students protested. The faculty union president blasted the trustees for their “complete arrogance and tone deafness.” Governor Jerry Brown questioned why Cal State presidents should be paid “twice that of the Chief Justice of the United States.” Ultimately, the public outrage encouraged Republicans in the State Senate to oppose the reconfirmation of Herbert Carter, chairman of Cal State’s board of trustees.

Carter is gone, but his successor hasn’t learned anything from the executive compensation scandal. “Herb Carter was basically the fall guy,” Bob Linscheid, the board’s interim chairman, bluntly told the Chico Enterprise-Record. The board has matched Linscheid’s talk with equally tone-deaf action. Trustees last month voted 10 percent pay raises—the maximum allowable under a rule the board passed earlier in the year to mollify critics—for the new presidents at Cal State’s East Bay and Fullerton campuses. “I’m just sorry we can’t pay them more because of the policy we adopted,” CSU Trustee Roberta Achtenberg lamented at the meeting.

Assemblyman Anthony Portantino, a Democrat representing La Cañada-Flintridge in Southern California, and Senator Yee are calling on Cal State administrators “to come clean with a complete and detailed look at just how CSU executives are paid.” The two Democratic legislators are hoping to “ferret out the truth,” which isn’t too much to ask, especially since Cal State’s motto is Vox Veritas Vita: “Speak the truth as a way of life.”

Related Articles

The left-wing theory driving Vergara ruling

A point that hasn’t been made nearly enough by the MSM is that the Vergara vs. California ruling rejecting the

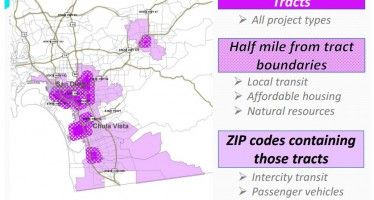

Counties vie for ‘disadvantaged’ cap-and-trade bucks

In the fictional town of Lake Woebegon, all of the children are above average. But in the real world

Life imitates sci-fi: Why CA pension crisis is sure to get far worse

The debate in California over public employee pensions has grown familiar in recent times. Those who demand reform finally appear