How Much Do Pensions Really Cost?

MARCH 11, 2011

By ED RING

Earlier this week the Sacramento Bee hosted a chat on the topic “Should States Rethink Collective Bargaining.” In addition to journalists from the Bee, participants included Steve Greenhut, editor of CalWatchdog.org, and Art Pulaski, the chief officer of the California Labor Federation, AFL-CIO.

During the hour-long discussion, the topic of public sector pensions came up a few times, and Pulaski stated that the average pension collected by retired state workers in California are not much more than social security. Referencing the chat log, he said:

ArtPulaskiCLF:

the average state worker gets a pension of $24,000 and often without social security. Not lavish by any means

Tuesday March 8, 2011 12:48 ArtPulaskiCLF

This is a profoundly misleading statement. When Pulaski, and others who share his perspective on these issues, use numbers this low, they are reporting an average that includes everyone on the CalPERS retirement rolls, even people who have barely vested their retirement benefit by only working five years for the state. Furthermore, this average includes part-time workers, and it includes long-time retirees who left the workforce before base pay and pension formulas had been increased significantly – and unsustainably – as they have in the last 10-15 years during the economic bubbles.

A more realistic way to gauge the fairness and financial sustainability of state worker pensions is to reference the average pension for currently retiring state workers who have logged 30 years of full-time work for the government. Using data from CalPERS annual report for the fiscal year ended June 30th, 2010, entitled “Shaping our Future,” (ref. page 151) the average pension for a state employee enrolled in CalPERS who retired last year after 30 years of service is $66,828 per year.

This amount, far in excess of the “$24,000″ claim by Pulaski, is based on data provided by CalPERS, and is further evidenced by evaluating the typical pension benefit formulas currently granted government workers in California. People employed by the University of California, for example, as can be seen on the “University Retirement Plan” (ref. page 13), will receive between 60 percent (30 years, age 55) and 75 percent (30 years, age 60) of the average of their final three years salary in retirement. Benefits for state and local public employees in California typically range between 2.0 percent and 2.5 percent times years worked, times their final salary.

For public safety employees, who comprise approximately 15 percent of the state and local public sector workforce in California, pension benefits typically are calculated based on 3.0 percent, times years worked, times their final salary. The labor agreement between Sacramento County and their firefighter union provides a representative example. (Ref. “Agreement between Sacramento Fire Fighters Union and City of Sacramento,” page 55.) For information on all bargaining units and their pensions in the City of Sacramento, refer to the links on their “City of Sacramento Labor Agreements” page. You will see that in the city of Sacramento, whose worker benefits are quite typical of the cities and counties in California, it is typical for workers currently retiring after 30 years to receive about two-thirds of their final salary in pension benefits.

To really understand what this means, it is necessary to come up with two additional estimates, (1) the average base salary for a government worker in California – which allows one to estimate the average pension of a retired government worker – and (2) the number of retired government workers. This allows one to calculate how much money is disbursed each year to pay retirement pensions to retired government workers. This amount, in-turn, can be compared to how much is being disbursed each year to pay retired private sector workers who collect Social Security.

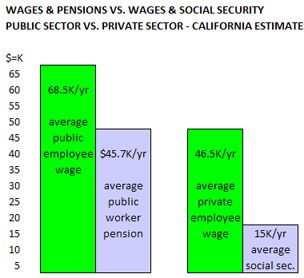

Using California as an example, and using conservative assumptions (because the CalPERS data already noted suggests the average career pension to be far higher than $46K per year), the following table illustrates how much the average government worker makes per year both while working and during retirement, and compares it to how much the average private sector worker makes both while working and during retirement. These figures dramatically illustrate the disparity between government worker compensation and private sector worker compensation. On average, government workers collect a base salary that is nearly 50 percent more than private sector workers during their active careers, then collect over three times as much through their pensions in retirement than retired private sector workers collect from social security. In fact, the average government worker’s retirement pension is equivalent to the average private sector worker’s base wages while still working!

The amounts presented in the above table are fairly easily calculated using core data that any reader is invited to verify for themselves. The average California state and local government worker wage of $68,500 per year is derived from U.S. Census Bureau data which can be found on the following tables “U.S. Census Bureau 2008 Public Employment Data Local Governments California,” and “U.S. Census Bureau 2008 Public Employment Data State Government California.” The average California private sector worker wage of $46,500 per year can be found from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics “May 2009 California Occupational Employment and Wage Estimates.” The average social security benefit for an average wage earner can be found on the “U.S. Social Security Estimated Retirement Payments Chart.”

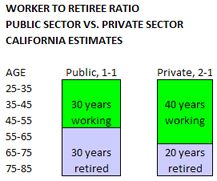

The cost to Californians of paying government workers, on average, a pension that is literally triple what the average private sector worker collects from Social Security is compounded by the fact that the ratio of government workers to government retirees is on-track to be 1-1, i.e., one worker for each retiree, whereas the ratio of active private sector workers to retired social security recipients is unlikely to ever dip below 2-1. This is because government workers typically work from ages 25 to 55, then retire for 30 years, and private sector workers typically work from ages 25 to 65, then retire for 20 years. An examination of projected age distributions in America for 2030, as documented on the U.S. Census Bureau’s International Database, indicates the United States is destined to have an even streamed age distribution, i.e., about 20 million citizens in each five year age group, which makes these calculations much easier. This disparity is illustrated in the table below:

What the above table demonstrates is the following: Notwithstanding investment returns, if there is only one active government worker – working 30 years – for every retired government worker – retired for 30 years, and if the average government pensioner receives a pension equivalent to two-thirds of what they made when they worked, then funding government worker pensions would require each government worker to contribute an amount equal to 66% of their salary towards supporting the retirees. By contrast, if at least two private sector workers – who work for 40 years and are retired for half that time – are employed for each one who is retired, and if the average private sector retiree receives a social security benefit equal to one-third of what they made when they worked, then adequately funding social security would require each private sector worker to contribute an amount equal to only 16 percent of their salary towards supporting the retirees. This reasoning holds enormous implications when assessing the relative long-term viability of government worker pensions vs. Social Security.

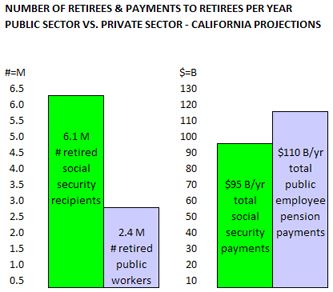

Perhaps the most dramatic illustration of the inequity of California’s government worker pensions averaging literally the same amount as what the average private sector worker earns while actively working is illustrated in the next table. The calculations are based on multiplying the average amount of the government worker pensions by the estimated number of retired government workers, and comparing that to the average amount of the social security benefit multiplied by the estimated number of retired private sector workers. To estimate California’s projected population of retired government workers, simply use the same number as their working population, 2.4 million, since on average they work 30 years and are retired 30 years. To estimate California’s projected population of retired private sector workers, similarly, just take the population of active private sector workers, 12.2, and divide by two, since on average they work 40 years and are retired 20 years. Data for these working populations can be found from the California Employment Development Dept., Labor Market Trends 2009.

On the above table, the green columns represent the projected number of retired social security recipients in California, 6.1 million, and the amount they will collect in aggregate in Social Security, $95 billion per year. The blue columns represent the projected number of retired government workers in California, 2.4 million, and the amount they will collect in aggregate in pensions, $110 billion per year. This is an astonishing projection. It indicates that the government will be spending more, in total dollars per year, to pay pensions to retired government workers, than it will be spending, in total dollars per year, to provide social security to retired private sector workers who are nearly three times as numerous.

To the extent these extravagant benefits have been approved by compliant politicians on behalf of government workers in other states, what these figures illuminate for California can be extrapolated to apply across the United States. To suggest that Wall Street pension fund investments are going to be able to make up for this disparity, and therefore somehow mitigate the burden this disparity places on taxpayers, is not only extremely debatable – because the high returns that pension funds delivered over the past 30+ years were driven by an unsustainable expansion of debt – but also specious. Because if Wall Street investments are the panacea, set to rescue taxpayers from the burden of supporting retired government workers, why are spokespersons for government worker unions blaming Wall Street at the same time as they fail to recognize that their pension funds are Wall Street?

If government worker pensions, whose solvency is currently guaranteed by taxpayers, are to be gambled on Wall Street, why isn’t the Social Security fund also gambled on Wall Street? Why do taxpayers bear the downside of the Wall Street manipulated economic meltdown not only for themselves and their own individual investments, but also take the hit and make up the difference for the government workers and their pension funds? Anyone representing government worker unions who claims Wall Street is both the problem and the answer should seriously examine their premises. And anyone who suggests government worker pensions are not extravagant, or do not place a crippling burden on taxpayers and government budgets, is not confronting the facts.

Ed Ring is the editor of http://unionwatch.org.

Related Articles

GOP lawmakers deliver key votes for tax extension

how to get your ex back Last month, Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown signed into law a $2.3 billion tax

Boxer-Feinsten water bill stresses conservation, not supply

There are two ways to manage water. One way is to capture more water and store it for dry years.

Regulators to consider breaking up scandal-plagued PG&E

A California Public Utilities Commission report that Pacific Gas & Electric failed to fulfill its responsibilities to properly maintain natural